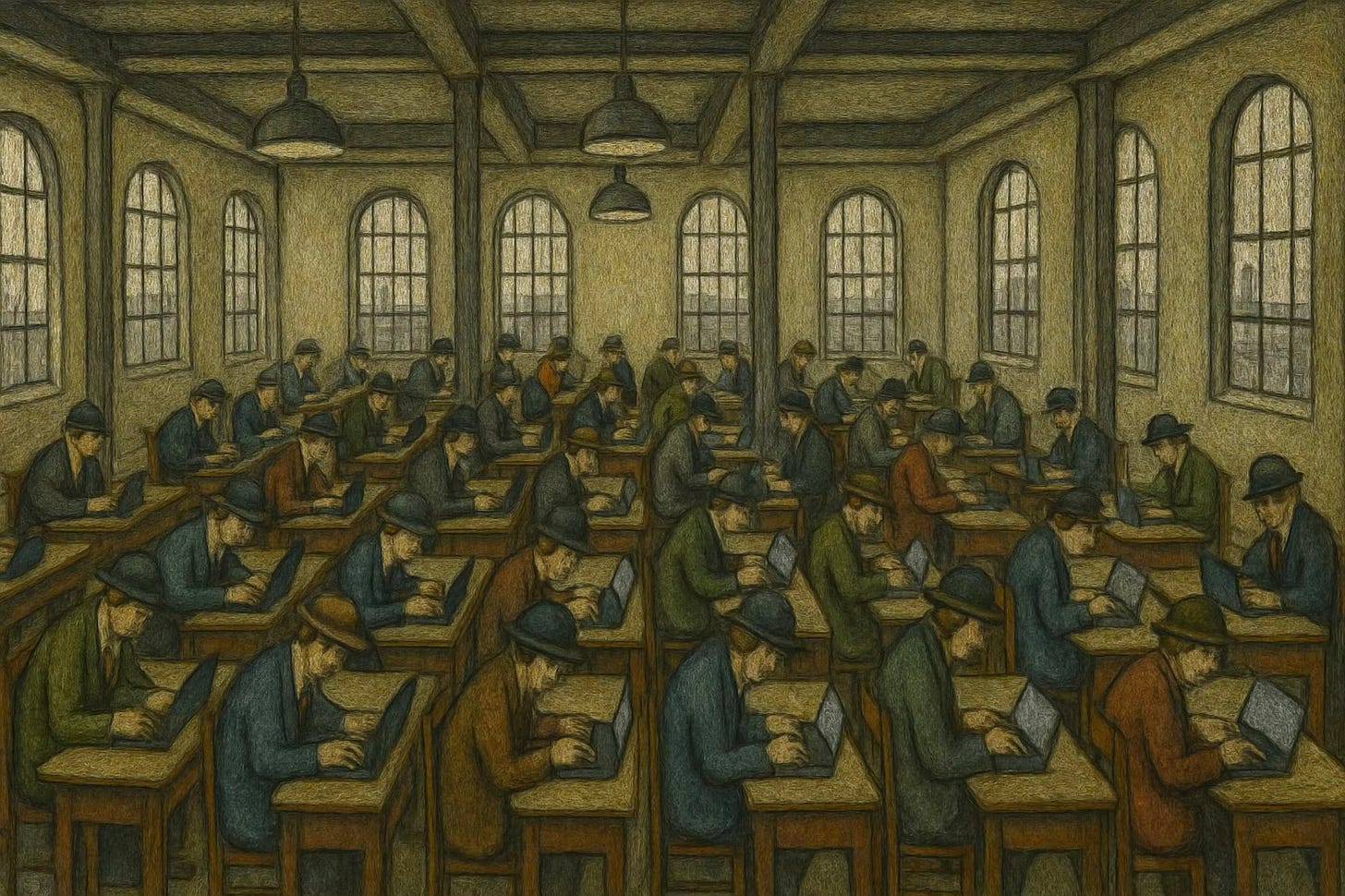

Can AI Help Reverse the Oversimplification of Management?

For leaders to be programmers of their organisational OS, they need AI's help in embracing complexity and reality, rather than relying on simplistic data proxies

As we look forward to a new year, it is worth zooming out momentarily from the frenetic race between AI models to focus on some of the enablers, blockers and wider changes that will determine whether organisations are able to use this technology effectively.

We now have a few studies that point to good but not great marginal efficiencies when using Generative AI inside existing business structures and management systems to speed up existing tasks. But whilst current LLMs and SLMs are more than good enough to support intelligent operations, the transformational potential of agentic AI depends upon readiness efforts in areas from technical and data infrastructure to organisation mapping, process discovery and explainability, and in particular, local training and context management.

At the infrastructure level, there are welcome signs that some of the technical enablers for agentic and enterprise AI are getting more attention, including interoperability with protocols such as MCP and a standard approach to defining agent skills.

Leaders as Programmers

But where is the shift in leadership and management that will be required to re-invigorate our tired bureaucracies and create intelligent AI-augmented organisational operating systems?

We have written about world-building this year as an important emerging leadership skill, and we are finding this to be an accessible and useful frame for leadership development in organisations seeking to pursue enterprise AI.

Tomasz Tunguz recently shared an interesting musing on context databases and why they are needed if we want to move away from brittle, deterministic automation to fully exploit the capabilities of enterprise AI.

Making the rules of the road explicit is a key management activity as we progress towards programmable organisations, and this is why we include leaders as programmers within our leadership development programmes and workshops. This is not the old idea that “leaders should learn Python”, but the realisation that clearly stated high-level goals and instructions linked to all their necessary context is probably how the programmable organisation will be operated and guided in the future.

We have argued for a long time that literate leadership (writing things down, collating knowledge and curating data) beats performative leadership (meetings, presence and a focus on simplistic decision-making) over the long run. Those leaders who have written things down and encouraged their teams to document their work in wikis, collaboration systems and knowledge stores will have a huge advantage, and the resulting content will give context databases a big head start.

All of this has major implications for L&D functions, and we are starting to see some of them trying to re-define their value proposition from content delivery to longitudinal support and product development.

How Can AI Make Management Smart Again?

If we are to develop the leadership organisations will need in the AI era, perhaps we should start by asking where things went wrong in the previous one.

Dan Davies’ excellent book The Unaccountability Machine provides some clues, and also hints at ways in which AI might make the theoretical notion of management cybernetics feasible as a practical way to run at least the basic functions of a complex organisation.

The book begins by looking at accountability sinks - structures (rules, algorithms, or market pressures) where decisions are delegated so deeply into a system that no individual human can be held responsible for the outcome - and their role in the 2008 financial crash. But it goes on to look at the way reductive abstractions drove post-war economics towards Milton Friedman’s doctrine of shareholder value-maximisation, which spawned value-destroying ideas such as the leveraged buyout industry.

But Davies also looks at management failings through the lens of cybernetics and specifically Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM), and how management’s reductive approach to complexity fell foul of Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety (for a manager to control a system, their “regulatory variety” must match the “variety of the system” they are managing). By using attenuators to simplify their picture of the firm, such as share price or quarterly sales reports, managers have made the organisation blind to all the other important data and signals necessary to guide strategy; plus, the signals they do use for strategy tend to be lagging indicators.

It might seem that AI and the algorithmic era will make this situation even worse and therefore we should return to an imagined ‘good old days’ of personal, accountable management. But in fact, enterprise AI offers better ways to cope with increasing complexity, and therefore a way to embrace it positively.

On the attenuation question, agentic AI enables us to maintain a detailed, objective picture of real-time operations within even a large, complex organisation, meaning the variety of the control system is able to match the variety of observable reality. If leaders really are too busy (or lacking the knowledge) to engage with reality, then AI is also pretty good at summarising information for them, but without needing to attenuate / throw away a lot of the richness as late Twentieth Century management tended to do.

A modern artificial intelligence system – a transformer recurrent neural network can take a large block of text and summarise it quickly. It can also expand a short instruction into a longer explanation. It’s practically designed for facilitating two-way communication between a mass audience and a smaller decision-making system. It would really be a generational shame if we ended up once more just using it to make our existing structures work faster – like bringing back Shakespeare, Machiavelli and Napoleon and setting them to work designing tax forms.

Anybody who has seen an important, expert-designed project or proposal for action reduced to kindergarten images and bullet points so that a senior leader with the attention span of a goldfish can “decide” will surely welcome the fact that we can summarise without attenuation.

Agentic AI can also help eliminate accountability sinks in several ways. For example, processes and rules of the road no longer need to be oversimplified to such an extent that people can be trained to follow them. Instead, we can write as many rules and exception handlers as we like, and leave it to the agents to ensure they follow them, with human oversight of the overall outcomes and the system. Plus, by automating the drudgery of basic work coordination (what Beer called System 2 in the VSM), people can spend more time focusing on big picture questions such as identity and purpose (System 5), which means Instead of being cogs managing spreadsheets, managers can return to being architects of the organisation’s mission.

Of course, this works only if we design our structures and rules with this in mind. The machine is only as good as what it ‘cares’ about. If we use AI to automate the same narrow goal of “maximising shareholder returns at any cost”, we will simply build a faster, more efficient ‘Unaccountability Machine’.

“The purpose of a system is what it does.” - Stafford Beer

“Nine to five, for service and devotion…”

One issue for both society and business that will start to assert itself in 2026 is the question of jobs. Recent job surveys reveal a bifurcation of the labour market. While mass unemployment has not yet materialised, the data shows that AI is hollowing out entry-level roles while simultaneously exacerbating a shortage of high-skilled talent.

AI critics such as the wonderful Cory Doctorow argue that AI is being sold on the promise of job cuts and cost savings, and that none of the surplus it produces will be returned to workers:

The growth narrative of AI is that AI will disrupt labor markets. I use “disrupt” here in its most disreputable, tech bro sense.

The promise of AI – the promise AI companies make to investors – is that there will be AIs that can do your job, and when your boss fires you and replaces you with AI, he will keep half of your salary for himself, and give the other half to the AI company.

But I think there is some win-win potential in the expected impact of AI on jobs. As Azeem Azhar shared in his 2025 in 25 stats summary, for the first time in 22 years, work-life balance has overtaken pay as the most important job factor, according to Randstad’s 2025 Workmonitor report. Indeed, perhaps the entire industrial era concept of jobs is a form of neo-feudalism that we should leave behind, assuming we can find other ways to fund basic needs.

As Antonio Melonio argues in a provocative post entitled The era of jobs is ending:

The system we built around jobs—as moral duty, as identity, as the only path to survival—is about to collide with machines that can perform huge chunks of that “duty” without sleep, without boredom, without unions, without pensions.

You can treat this as a threat.

Or as a once-in-a-civilization chance to get out of a religion that has been breaking us, grinding us down, destroying us for centuries.

But at the same time, we have the opportunity to reshape those jobs that are not at risk through finding creative and human ways to combine people and AI. There is a lot of thought going into the skills needed for people to make the most of this, and people are starting to explore how to quantify human-AI synergy to find the optimum collaboration. In a situation where skilled workers are at a premium, this all suggests that some jobs will get better and become more interesting.

But let’s not pretend that this will not be very disruptive for many people’s lives, especially in a world where housing has become an asset class rather than a basic right. This will need a policy response as well as businesses taking some responsibility for the gravity of the shift away from full employment as a realistic goal.

I already advise my mentees only to consider taking a job as a stepping stone to better things, and to avoid getting trapped in employment whilst developing their own independent income sources; I expect employers will need to work hard to sell the idea of a 9-5 to the next generation.

Finally, on the subject of work, we will hit the pause button and return in the new year. I have a large section of the very best Tuna toro and some lesser known Spanish red wines that are crying out for experimentation.

But for now, we wish you all a wonderful festive season and a happy new year.