Why Does Individual AI Literacy Fail to Translate into Organisational Impact?

Why Enterprise AI demands leadership readiness, not just technical adoption

💡 Start the new year armed with leadership techniques and methods. All new premium subscriptions are discounted by 25% during January!Many organisations have now crossed a visible threshold in their AI journey. Access is widespread, and the tools are familiar. People can analyse, draft, synthesise, and explore at a pace that would have been unthinkable even a year ago. And yet, for many leadership teams, the sense of organisational progress remains stubbornly unchanged.

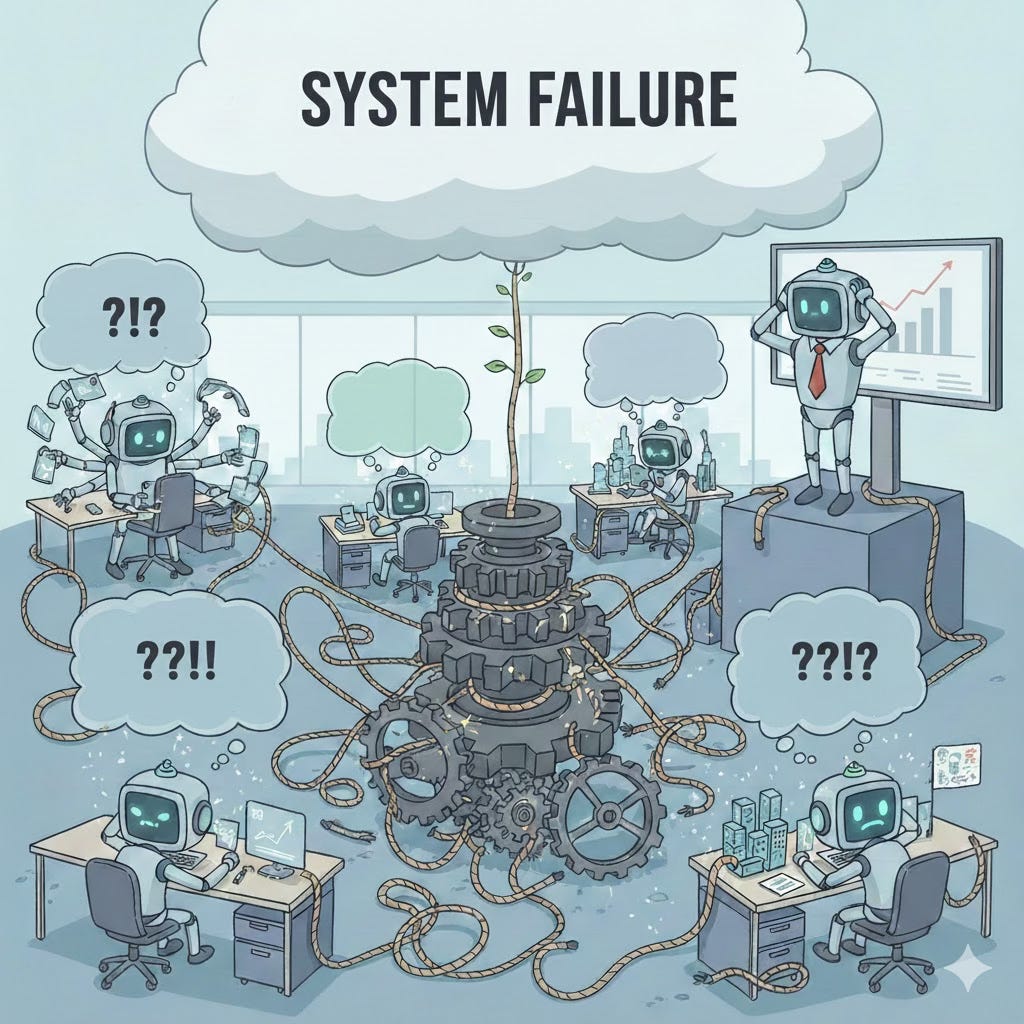

Decision cycles do not shorten in proportion to individual speed. Coordination is no easier than before, and strategy still degrades as it moves through the organisation. In some cases, leaders describe an increase in activity without a corresponding increase in clarity or momentum.

This gap between individual literacy and collective impact is often framed as a tooling problem or a capability gap - the assumption being that something is missing at the level of adoption, training, or integration.

But what AI is actually revealing is something more fundamental.

Why “everyone has Copilot” rarely produces productivity

From a leadership perspective, the symptoms are familiar. Teams appear busy, outputs multiply, updates arrive faster and in more polished forms. Yet progress at the organisational level feels uneven and fragile.

This is not a new phenomenon. High-performing individuals have always been capable of outpacing the systems around them. What AI changes is the scale and visibility of this mismatch. When individual throughput increases sharply, the organisation’s existing coordination mechanisms are placed under strain. Leaders tend to notice this first in places they already recognise. Meetings fill with material but resolve little. Strategy documents proliferate without increasing alignment. Initiatives stall because nobody is quite sure who has the authority to make the final trade-off.

AI removes the friction that once masked these conditions, compounding them further.

Roles that seemed clear on paper turn out to rely heavily on personal interpretation and historical relationships. Processes designed for predictability reveal how much they depend on shared context rather than formal steps. Authority that was exercised tacitly becomes a bottleneck when decisions arrive faster than consensus can form. Accountability, already diffuse in many large organisations, becomes harder to trace when work is produced collaboratively and iteratively.

Why social friction becomes the real bottleneck

As individual work accelerates, organisational performance is constrained less by technical capacity and more by social dynamics. Faster individuals do not always lead to faster decisions, since decisions are collective acts shaped by trust, clarity, and shared judgment. Without explicit agreement on who decides and how, speed at the edges creates pressure at the centre.

Better outputs do not guarantee shared understanding. Leaders are often presented with polished artefacts that conceal unresolved disagreement or divergent assumptions. This creates a false sense of alignment that only unravels during execution.

More content does not create clearer intent. When everyone can generate high-quality material quickly, intent must be carried by context, framing, and narrative rather than volume.

From a leadership standpoint, this is often where AI begins to feel disappointing. The technology works, but the organisation does not improve.

One reason social friction is frequently misdiagnosed is that it rarely announces itself directly. Leaders experience it obliquely, as drag, noise, repetition, or a persistent sense that effort is not compounding. Each executive role tends to encounter social friction in different forms, shaped by where it sits in the organisation’s coordination landscape.

CEO pain points: strategy that travels poorly

For CEOs, social friction often appears as a gap between strategic intent and organisational motion.

The strategy is clear at the top. The narrative is coherent. Yet as it moves through layers, functions, and initiatives, it fragments. Different parts of the organisation pursue locally sensible interpretations that do not quite add up. Progress is reported, but coherence remains elusive.

Before AI, this showed up as slow execution or inconsistent prioritisation. With AI, it shows up as acceleration in many directions at once.

The friction lives in unspoken assumptions about trade-offs, risk appetite, and what must remain invariant as teams adapt.

A useful micro-technique here is to articulate not only what the organisation is trying to achieve, but what must not be optimised away. Making a small number of strategic constraints explicit gives faster actors something stable to orient around, even as methods and tactics evolve.

COO pain points: flow that breaks at the boundaries

COOs tend to experience social friction as interruptions to flow.

Processes appear sound in isolation. Metrics look healthy. Yet work slows at handoffs, escalations arrive unpredictably, and teams quietly route around formal mechanisms to get things done.

Before AI, this was often managed through experience and informal fixes. With AI, those hidden seams become stress points as activity speeds up.

Here, friction tends to live in unclear authority boundaries and escalation paths that rely on personal judgment rather than shared design.

A practical micro-technique is to treat escalation as a designed feature of the system rather than a sign of failure. Defining in advance which thresholds trigger human review, and why, turns escalation into a predictable coordination move rather than a difficult social negotiation.

HR pain points: accountability feels diffuse

For CHROs, social friction often surfaces as ambiguity around accountability.

Decisions are made, but ownership is difficult to trace. Performance conversations gravitate toward visible activity rather than quality of judgment. Learning investments proliferate, yet behaviour shifts unevenly.

These patterns existed long before AI. What AI changes is the visibility of contribution, making it harder to distinguish between effort, output, and responsibility.

Here, friction often resides in implicit norms about who is expected to exercise judgment and who is expected to comply.

One useful micro-technique is to separate responsibility for decision quality from responsibility for decision outcome. Making it legitimate to examine how judgments were made, not only whether results were favourable, supports learning without triggering defensiveness. This becomes essential as AI-generated inputs enter the decision process.

L&D pain points: learning that does not accumulate

L&D leaders frequently encounter social friction through learning that fails to compound.

People attend programmes. Skills improve locally. Yet the organisation does not appear to get collectively smarter. Knowledge remains trapped in individuals or teams, and hard-won insights are relearned rather than reused.

Before AI, this was frustrating but familiar. With AI, the risk is that individual learning accelerates while organisational memory remains thin.

The friction here lies in the absence of a shared language for judgment, reflection, and decision rationale.

A useful micro-technique is to design learning moments around interpretation rather than information. Capturing why a decision made sense in context, not just what was decided, creates material that can inform both human learning and machine-supported memory over time.

What this means for AI adoption strategies

What many leadership teams are discovering, often indirectly, is that AI does not simply stretch existing systems, it reveals how much organisational coherence was previously being held together through personal authority, informal influence, and tacit understanding.

For a long time, this worked well enough. Shared history compensated for ambiguity. Experience filled in gaps that were never formally designed. Leaders could rely on intuition, relationships, and pattern recognition to keep the organisation roughly aligned, even when roles, processes, or decision rights were imperfectly defined.

As individual contributors begin producing high-quality work faster than the organisation can interpret, decide, or align around it, those informal mechanisms start to strain. Gaps in coherence become visible rather than hidden. This is not because leadership has failed, but because coherence has rarely been treated as something that must be deliberately designed for, maintained, and renewed.

Through this lens, AI adoption reframes itself. What first appears to be a technology challenge becomes a leadership maturity challenge. Not in the sense of individual capability, but in the collective ability to sustain shared intent, judgment, and coordination under conditions of speed and complexity.

Coherence is not owned by any single role. It is produced through many small acts of alignment across the system. Yet different executive roles encounter its absence in different ways, depending on where they sit in the flow of decisions, accountability, and meaning.

This is why social friction feels different at the top of the organisation than it does in operations, people systems, or learning environments. And it is why the work of restoring coherence cannot be generic. It must be grounded in the specific coordination challenges each leadership role is already living with.

Techniques that reduce social friction

If the constraint is social rather than technical, the techniques that matter look different from traditional AI adoption playbooks, focusing less on individual skill and more on collective legibility.

Let’s look at three leadership techniques that can help improve collective legibility and context:

Creating Legibility through Decision Provenance Mapping

Ensuring shared mental models with Assumption Walkthroughs

Enabling collective sense-making using Decision Reflection Loops