Claude Code, but for Management

AI-enhanced software development has shown what's possible; doing the same for the management of process work is also possible if leaders can focus on what matters

In the past couple of weeks, more developers have declared that Claude Code, the leading AI model for software development, is now good enough that they no longer need to code manually. This is quite something, and if Claude Code can live up to this promise, this will have implications not just for software development, but also for how we think about the wider role of AI in enabling smart, programmable organisations.

As ever, Simon Willison was quick to share a comprehensive first impressions analysis upon its release in late October, and this positive view of its capabilities has been echoed by most analysts and commentators since then.

The creator of Claude Code, Boris Cherny, recently shared a useful long reflection on how he uses the tool, and also confirmed that the later release of Claude Cowork (a computer use wrapper for Claude Code) was achieved in under two weeks, and entirely written by Claude Code.

There are many reasons why Claude Code is so good, but Ethan Mollick touched on a couple of important aspects in his own account of using it, namely the architecture of Skills (each with their own guidance) and the ability to compact and summarise context when the context window becomes too full, which is a common pitfall of LLMs in general.

So if that is what AI tools can do to enhance and automate modern software development, then why is it so hard to galvanise leaders and managers inside our organisations to do something similar with the knowledge, processes and workflows that underpin the world of work?

Business Planning as Code Specs

Antony Mayfield’s newsletter touched on this topic last week, musing on what we can do with the tools we ‘steal from coders’ and how we should treat knowledge engineering like software development. To illustrate this idea, Antony reflected on the primitive nature of business plans inside large organisations, and how a knowledge engineering approach could improve them:

Like novels, business plans are not completed; they are abandoned. Even in the largest corporations, where leaders assemble for strategic planning sessions to thrash out the final plan, insiders will tell you the plan is what is left standing at the end of the week, when all of the different stakeholders no longer have the will to argue any longer …

Thinking of a business plan like a computer operating system is freeing (you accept it will have bugs that need to be fixed) and de-stressing. You can have multiple people working on different parts of it and – because software engineers do this all the time – there is a system for making the pieces fit together and make sense (it’s called a merge).

This is still only an emerging practice among leaders today. There is so much organisational debt and outdated ways of working at senior levels that act against its adoption among more operational managers, but we are seeing some evidence of change.

Ultimately, when everybody has access to similar models, the edge (or in VC terms ‘the moat’) is context, as Saboo Shubham (an AI product manager at Google) wrote whilst on the Xitter:

The models are commoditizing. Prices are dropping. Capabilities are converging. What was SOTA a few months ago is now available to anyone with an API key.

So where does the real alpha come from?

Context.

The team that can externalize what they know and feed it to agents in a structured way will build things competitors can’t copy just by using the same model.

For leaders and managers, this means the simple task of writing things down and documenting value chains and processes is all they need to really start to master enterprise AI proficiently, as we have written about previously.

The next step is connecting those processes to agents and to each other. For processes and workflows to be programmable, they first need to be addressable - and ideally composable.

Rudy Kuhn of Celonis recently argued that the lack of composability in enterprise process architectures is holding them back from realising the promise of enterprise AI, and needs to be tackled if we are to see real AI-enabled business transformation:

For many organizations, this progression mirrors the broader evolution of their processes. They moved from analog to digital, from digital to automated, from automated to orchestrated. The shift toward composable and increasingly autonomous operations is the next logical phase. It reflects how companies already work in practice, even if their formal structures have not yet caught up. It also signals a shift in how transformation itself must be understood. Instead of forcing new behavior through large, one-time programs, organizations are beginning to redesign the very capabilities that make those behaviors possible.

And yet … and yet … most learning and change programmes inside large organisations are still focused on tool training. Executives are taught LLMs and prompting, and external ‘experts’ clap like circus seals when they are able to generate a picture or summarise a report.

But whilst we can forgive executives not knowing how to prompt the latest LLM chatbot, isn’t context, process documentation and organisational architecture something they should know already? You know … like … how their organisation works?

If they can’t put the PowerPoints down for a second to do the apparently exhausting work of writing things down and providing clarity, then perhaps Joahnnes Sundlo will have his wish:

Maybe we need to find new roles for human leaders. Maybe management shouldn’t be about work distribution anymore. Maybe it should focus on coaching, support, development. The traditional management role has its roots in military organization and the Industrial Revolution. Maybe it’s time to challenge those old, sacred organizational structures.

Can we do this smarter? More effectively? I think we have to at least start asking, discussing and shape what the future of our leaders should be.

2026 seems like a good year to begin.

Smol, open models you can own and control

Context and knowledge engineering will also help us make the most of the many small models (SLMs) that are now freely available. These have the potential to be both cheaper to run and also more reliable and less error prone because they are focused on tightly-bounded knowledge domains.

As Tabitha Rudd AND Seth Dobrin write in Silicon Sands, the three big reasons why more attention will be paid to enterprise SLMs this year are:

Privacy and Data Sovereignty

Cost Predictability

Reliability and Offline Operation

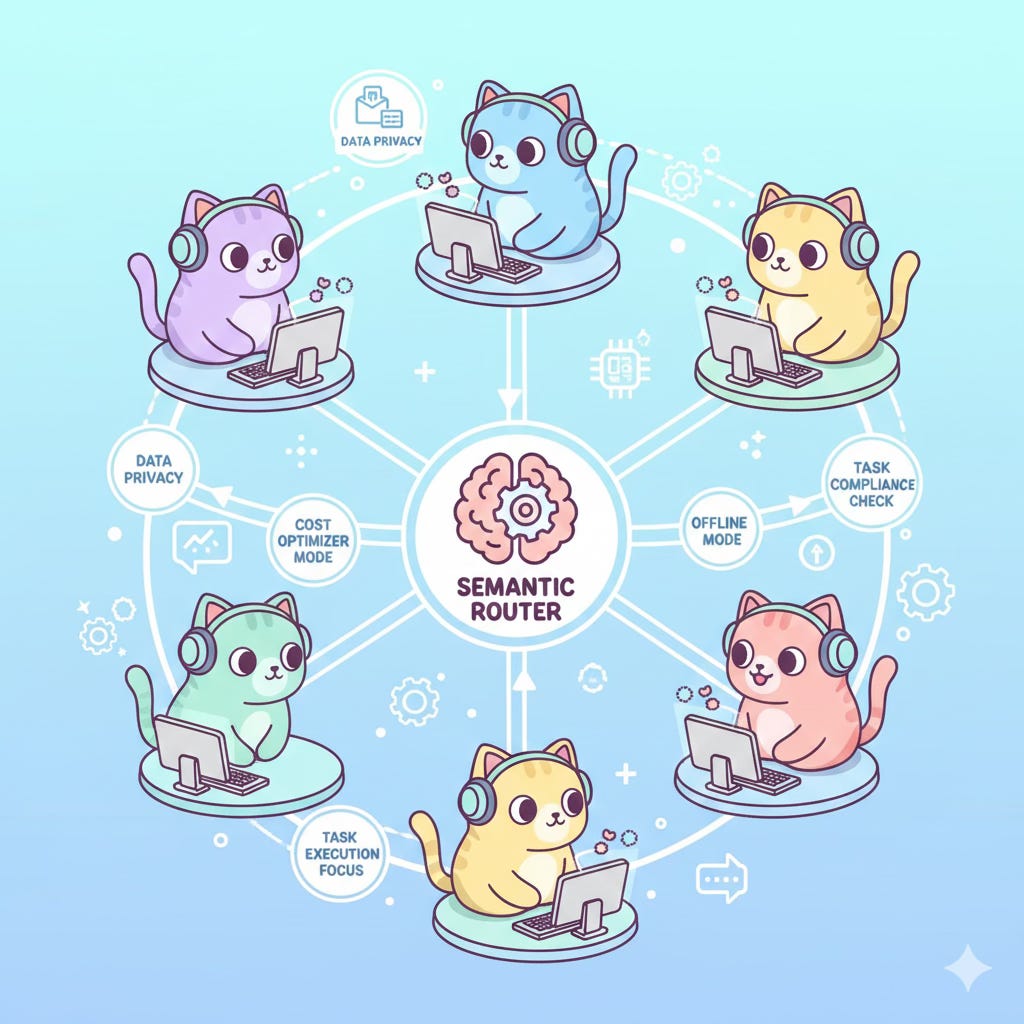

Using SLMs for agentic AI makes a lot more sense than trying to debug hallucinations or errors in agents based on large models, and as Gokul Palanisamy argues, this suggests a more devolved architecture using routing agents to integrate multiple small, specialised agents is needed:

The fix is not replacing LLMs with SLMs; it is stratifying them behind a Semantic Router.

A Semantic Router is a thin, model‑agnostic governance layer between the user and your model stack

I’d argue that there will be few if any enterprise use cases that will require a bleeding edge LLM. And if you can wait six months for an open-source option to catch up (likely from Nvidia at this point) why would you blow your cost curve on a high-end model?

You can use a series of open models to form an agentic system. The whole is greater than the parts and the parts need to be cheaper.

At the same time, there is also more emerging evidence that alternative training methods such as convolutional neural networks, inspired by biological insights into brain development, can achieve strong results with significantly smaller datasets, especially for world models. This could open the way for individual firms to have auditable control over their own SLMs and agents in areas where compliance, security and safety are paramount.

CIOs and CDOs have a lot on their plate deploying AI tools and working on the supporting infrastructure; but as they get on top of this, I expect to see more small, owned, open models being trained by individual firms and guided by their own specific context engineering.

These could also be a key building block for digital sovereignty at the sector, national and supra-national levels, not just within individual firms if, for example, your continent faced an existential threat from a powerful rogue state that also happens to own most of your digital infrastructure.

As ever, the critical IP and the value lies in the context and application layers, not the models themselves, and so the quality of knowledge and intelligence could still beat brute force compute.

Perhaps context graphs really will be a trillion dollar opportunity, as Foundation Capital recently argued…